Reload to That Day

The 1994 dating sim Tokimeki Memorial is about reliving high school, but it’s also about wanting to return to a good day. As the seasons change in the game, the background music shifts. I looked up the names of these on the soundtrack, and they are so charming it hurts. The fall music translates to “Footsteps on Dead Leaves.” There are two winter songs, “White Breath,” and “Oranges at the Kotatsu.” It’s the last one that really sets the mood—the image of a teen or child sitting under a heated table with a snack and no need to move from the toasty safety of it all. These evocative titles speak to Tokimeki Memorial’s entire spellbinding appeal. It creates the kind of atmosphere and just specific enough moments that linger even after the sharpness of memories fade, the kind of details that make you believe something was a 100% good day even if it wasn’t.

A spiritual companion to the game could be the anime Kimagure Orange Road, which aired from 1987-88. The 48-episode series is a zany slice of life romance about a teenage boy, Kyousuke, who happens to have supernatural powers. The powers are both important and completely beside the point. They are important because he uses levitation to save a beautiful girl’s hat from being carried off by the wind and unimportant because everything that happens with that girl is human, teenage stuff. The story is a love triangle sustained through wacky plot twists and miscommunications. We always know that the real romantic lead is Madoka, the owner of the hat. Her rival, Hikaru, is just sort of there through her own sheer force of will.

Although the kimagure (“capricious”) in the title refers to Madoka, it also works as a comment on the beautiful and selective lies of memory. It doesn’t feel like a show about high school students as much as a show about nostalgia for those years. Its follow-up movie, Ano Hi ni Kaeritai – “I Want to Return to That Day” – presents an alternate version of the story in which the love triangle comes to a head earlier and more realistically. If the series is a fizzy, sherbet-hued version of romantic drama, the movie is the urgent and distressing nowness of teenage angst. The characters in the movie fret, fight, and cry. The Kyousuke of this version is both guiltier and meaner than his anime counterpart. Hikaru’s voice actress steals the show with her gut-wrenching heartbreak. The day the characters want to return to could be any day before the conflict boils over, or it could be the entirety of the original series, and the feeling of watching it. In Tokimeki Memorial, the game’s story itself is the day, and playing it is the desire to return. The longing seems built-in, your adolescent avatar nostalgic for his life even as he’s living it. It’s as if game’s designers and all its inner workings know you are too old for the simulated experience you came for.

At the game’s Kirameki High (delightfully, “Sparkle High” in English), there is a superstition about the densetsu no ki: tree of legend. If you confess your feelings to someone under the tree, you and your now-not-secret crush will enjoy a lifelong romance. It serves not just as lore, but a baked-in explanation for why characters act so carefully and naively about love. I did not have a good high school experience, and you would not only have to pay me but offer me proof of alternate dimensions to get me to return. My teenage years were marked by a sordid, if common and suburban, loss of innocence. The very naivete that’s supposed to emphasize the characters’ youth seems, ironically, something that could only be written by an adult. Only someone with a great burden of regret would wish their life had instead been guided by a magical tree. Magic is usually just what we decide to assign outsized importance to, and I wish I had assigned it to different things. I imagine it’s the same for a lot of players, even the original target demographic: a college or so aged young man in Japan in the mid-1990s. The high school life captured in Tokimeki Memorial was much closer to their reality than mine, but it’s still a fantasy. I can’t say whether the shorter distance between real life and the golden hour version of it in the game makes it more or less painful. You’d have to ask a Japanese man who is now creeping towards middle age. I wonder if he would have a different perspective on the game than he had at 18 or 20, or if it would be almost unchanged. Perhaps a vulnerable boyishness would break through a grown man’s features in longing for a past that never, but almost, maybe with a trick of the light, existed.

While Tokimeki Memorial takes place in the mid-90s, its sensibilities are that of a time just past, which can seem the furthest away of all. The world of Japanese music was already entering an era where female artists had more control over their own image and were creating edgier, more experimental sounds. With the exception of one or two characters, the girls in Tokimeki Memorial conform instead to the trappings of 80s pop idols. I can easily understand how powerful the allure of these girls could have been to teenagers and young adults in 1994. I was born in 1991, and I have an achingly strong attachment to pop culture from my early childhood. For a young adult in 1994, the beautiful, soft image of an idol like Seiko Matsuda would have loomed large at a time in his childhood where things left strong impressions but weren’t complicated by adult anxiety. The recent, blink-and-you-missed it past can often feel the most painfully distant.

Tokimeki Memorial uses dating as its framework for experiencing high school but it’s also about making the most of a fleeting three years in every facet of life. Opportunities to get close to girls happen at a series of essential Japanese high school events: sports day, the school festival, the class trip, or a club retreat. But the big idea of “perfect school life” still has to be funneled through the constraints of game mechanics. Tokimeki Memorial was not the first dating sim, but it is the most important. As a genre, dating sims have long been misunderstood as simplistic, juvenile, or even perverted. Maybe that used to be fair. The pre-Tokimeki Memorial sims did tend to involve sex scenes as rewards for “winning” a girl. They’ve become more popular in western countries thanks to wider translation efforts and games that take inspiration from them, but dating sims remain a niche genre. Still, many if not most people who have played even a handful of games have played one that was influenced in some way by Tokimeki Memorial.

In the original Tokimeki Memorial, there are twelve dateable girls (plus one secret option). To say there’s something for everyone would be untrue. There’s something workable for everyone attracted to a narrow and mostly traditional range of feminine archetypes. There are three sporty girls, but even the most tomboyish among them has a secret girly side. The best birthday gifts for this particular girl are hyper femme clothes and accessories. Unlocking the secret character involves calling the popular rich kid at school over and over until you discover that he is, in fact, a girl. If you date the computer club’s mad scientist, maybe the most genuinely weird personality, you can catch her sighing with melancholy on the school roof. The romance story lines of the characters who seem the closest to subverting any kind of standard of femininity tend to be about uncovering vulnerability that is, in this game, the most feminine trait of all.

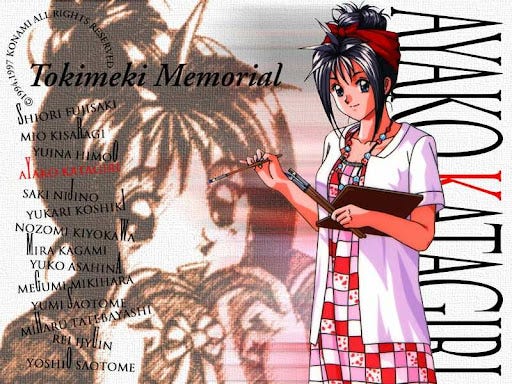

I decided that the girl I would try to end up with was Ayako Katagiri, a bold girl with a blueish-black topknot piled effortlessly on her head. Ayako paints in her spare time, plays in the brass band, and has a style that’s more eccentric than cute or sexy. She dresses a little like Denise Huxtable—baggy button-ups, oversized jewelry, and a visor and ripped vest in the summer. Ayako could, today, be the coolest girl milling around St. Mark’s Place on a Friday night. It seemed a little magical that Ayako’s birthday is September 30, 1978 – my husband’s exactly. Her signature quirk is peppering her speech with English phrases, like always ending dates with “sooo fun!” I would be friends with Ayako. What I’m not sure of is whether an awkward teenage boy would be able to keep up with her.

I thought I would have no trouble dating the girl I wanted in Tokimeki Memorial. Not because of any feminine intuition on my part, but because I knew which stats (art, trivia, appearance) to focus on. I also figured it wouldn’t be a huge mystery to pick dialogue options that Ayako liked. I actually messed up an embarrassing amount. At the art museum—one of her favorite date spots—she said that she wished she were as talented as the artists on display. The first option was to tell her “you are talented!” The last was, to the best of my reading comprehension, “can’t anyone do that?” The middle option was to tell her “you can be if you try hard.” The first choice seemed patronizing and the last rude, so I picked telling her to try harder. I thought that, as an aspiring artist herself, she would appreciate the honesty that great artists must work at it. I was wrong. She grumbled at me. On a repeat date, I chose to tell her she was talented. She smiled, and my character thought to himself that he made a “relatively good” impression. Now I’m wondering if, in its irreverence, “can’t anyone do that?” would have made her laugh. At the planetarium, Ayako marveled at the beauty of the star show and I told her it was “just her light.” Even as I picked it, I had a feeling (and maybe this time it was feminine intuition) that she would find it insultingly corny. It was like I was briefly possessed by the spirit of my clueless, teen boy avatar. She was, as I already predicted, unimpressed.

Meeting Ayako is triggered by your art stat reaching a certain number. My avatar ran into her one day after school and she told me to check out the art room if I felt like it. I responded something like, “maybe I will feel like it.” Unlike some dating dims, my avatar feels distinctly separate from me as the player. I wouldn’t ever say something like “maybe I will.” In Tokimeki Memorial, you can choose how to spend your time, what club to join, who to call, dialogue options on dates, and other assorted small choices, but many scenes play out with no input from me. Regardless of whether I’m currently dating another girl or even like Ayako, my avatar will answer in this adolescent attempt at smoothness. Rather than embodying a character, I’m guiding a hapless boy who is learning to develop his own tastes. Whether or not I, or he, is interested in Ayako, he is interested in the idea of girls and riding high on one approaching him.

My character’s automatic semi-flirting with Ayako didn’t bother me, but other girls kept showing up. First, Saki Nijino, manager of the baseball club, wanted to meet me. As class was ending one day, Saki introduced herself and told me I had guts and that together we could go all the way to the national tournament. My Americanness worked against me here because the charm of the dialogue was lost on me. What she said, specifically, was that we could go to the Koshien, a historic tournament hosted in the Koshien Stadium in Nishinomiya, Japan. For a Japanese player, the line would have immediately conjured nostalgia and images associated with this famous sporting event, maybe even what teams competed in their own high school years. But I had to spend ten minutes looking up the kanji and reading the Wikipedia entry for the tournament. It’s a special moment that is inevitably lost in not only translation, but any non-native experience. Saki soon started asking me to walk home with her and out on precious weekend dates. When the game came out, Saki was the second most popular heroine. She’s perfectly nice, but her unrelenting encouragement and gameness for every activity was off-putting to me.

Every girl is an archetype and an ideal, but Saki’s cheer leading struck me as especially over the top. Saki is a girl who will always overestimate you yet never hold the truth of your capabilities against you, and furthermore will always reassure you that somewhere deep down you actually are as great as she thinks you are. I lose patience with this kind of communication in real life. The inauthenticity of a friend insisting that I’m special and talented in a way that files off the real, rough edges of my personality and struggles always makes the chasm between intentions and true communication feel especially wide. When playing Tokimeki Memorial, I do see my avatar as separate from me. He doesn’t have to have the same taste in girls or friends that I do, but my revulsion for overwhelming positivity is too strong for me to allow my character to brook much of it.

Saki aside, I spent a lot of time fending off two of the wrenches the game throws into even the best time and emotion management strategy. Their names are Yumi Saotome and Megumi Mikihara. Yumi is the younger sister of my avatar’s male friend, Yoshio. Yoshio is more of a gameplay feature than a character. He is the school’s resident girl expert, keeping a notebook of phone numbers, hobbies, birthdays, and worst of all, measurements. It’s disturbing to imagine a high school boy caring about whether a girl’s waist is 59 or 60 centimeters. His sister is perky, easy to lead on, and quick to bomb you if she feels ignored. Bombs are an added difficulty that are infamously tricky in the original Tokimeki Memorial. If a girl’s name has a bomb beside it, you have a short window of time to placate her. Aside from calling Yoshio to ask him how the girls are feeling about you, bomb warnings come in the form of a girl meeting you after school, frowning or scowling, and running away. If the bomb goes off, she tells her friends you’re a jerk, affecting their relationships with you. Letting more than a few bombs go off is a good way to get the game’s bad ending, where nobody confesses to you. I suppose this is one of the most inherently sexist facets of Tokimeki Memorial, since the whole balancing act is a gamification of the stereotype that women are emotional, gossipy, and vindictive.

My other albatross, Megumi, is also maddeningly easy to date. She is the shyest girl. The best gifts for her are as soft as her affect: items like rabbit gloves and stuffed animals. She speaks in an airy, apology-steeped voice. As soon as she is introduced, there’s nothing you can do about Megumi entering the rotation of girls who will feel potentially neglected by your character. I do not enjoy her personality. Like Saki, she seems to be playing into the idea of an “easy” girlfriend. But unlike the encouraging, constant ego boost of Saki, Megumi is the girl who will never, ever make you feel like you should work harder. I felt almost no spark of specificity in her needs and expectations for a boyfriend. The only thing that came close to making me like her was a scene I got in my second play through, where Megumi finds a stray kitten on the way home from the Christmas party. What the functional difference for her between my avatar and the kitten was, though, I couldn’t say. My downfall here is that if you turn Megumi down for a date or refuse to walk home with her, she looks utterly crestfallen. I should have been playing the mercenary game of keeping her just satisfied enough not to bomb me, but I went too far out of my way to not hurt her feelings. At the end of my first play through, it was Megumi waiting under the tree. In her confession, she used the word hazukashii—embarrassed—far too many times.

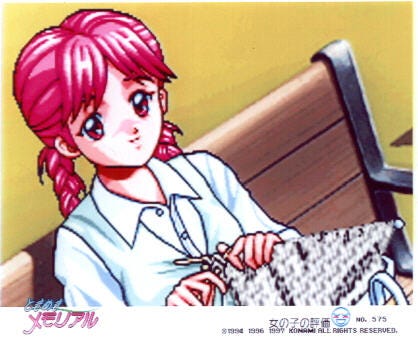

I started the game again, planning to try for Ayako once more. For kicks I messed with different stats than the previous play through, focusing more on exercise and appearance than studying in the early months. As a result, I met a girl I had not encountered before: Yukari Koshiki. Yukari is one of the sports girls, but her sportiness is in club affiliation only. Her actual role is to be the game’s yamato nadeshiko, a polite and traditional Japanese beauty. Like Megumi, she has a soft voice, but instead of a shy simper, Yukari’s is deliberately dreamy and slow. She uses formal speech that gestures to her sheltered and privileged background. It took me a long time to get a handle on how to talk to her. At the art museum, telling her that practice makes talent just makes her sigh a spacey “oh well.” For most girls, milquetoast statements of agreement will not impress. Yukari, however, is thrilled to hear that yes, koalas are indeed cute. At the aquarium, she said she wanted to become a fish and swim around in a daze all day. She wasn’t ambitious, nor did she want to be. She was pure vibes. In all my mediocrity, I was enough, just as long as she was enough too. This was the critical difference between her and Megumi. Yukari was definitely not going to get bent out of shape trying to please anyone.

Still, I got close to Ayako again. This time she was in the art club, not the brass band, and she gave me warm but constructive advice on painting during the club retreat. She brought me birthday gifts and showed up at my house on New Year’s Day. I even got a scene that I hadn’t encountered in the first game: catching her in her school swimsuit, skipping gym class because she was afraid to get in the water. But while I saw other girls as a nuisance in my first play through, I was truly torn this time between Ayako and Yukari. Yukari was the easier girl, definitely, but she was genuinely charming and weird. I took her to the botanical garden in the spring and got a special scene where she pointed out how interesting and cute some bizarre-looking hanging plants were. It endeared her to me. Where Ayako’s theme music is a brassy funk tune that fits the game’s 90s setting, Yukari’s is a slow, almost spooky Japanese-instrumented melody. Even the song titles speak to their personalities. Ayako’s, like her penchant for English slang, is “Boy Friends.” Yukari’s is “Kago no Naka no Kotori” - “little bird in a basket.” Ayako is, if not that much like me, like girls I recognize and feel a kinship with. I have nothing of Yukari’s unforced, preternatural chill. I am not a person who seeks out “soothing” experiences in gaming, but dating Yukari made me kind of understand why escapism can be a worthy goal. When she spent a park date knitting a sweater and gave the finished product to my avatar as a gift a few months later, I was truly touched. Without realizing it, I had been swept up in a fantasy, thinking about what it would be like to receive a handmade gift from a high school sweetheart. Or, more powerfully, what it would be like to be the kind of teenage girl who happily knitted handmade gifts.

I went into graduation day with both Ayako and Yukari in “tokimeki state,” indicated by a blushing face icon next to their names. My stats were well within the range for each of their specific ending requirements. Every ending of Tokimeki Memorial starts the same way. The character gets an unsigned note in his desk asking him to meet its writer under the all-important tree. You run towards a silhouette. The camera pans up slowly. In my case, I didn’t know who it was until the bottom of Yukari’s hot pink braids came into view. I was content with this. At some point on my dates and walks home with Ayako, she told me she was planning to study abroad in France after high school to work on her art. It struck me as fitting that I didn’t end up with the girl who has bigger things happening in her life than believing in lifelong love with a chaste high school boyfriend. Ayako is one of the only girls who seems truly contemporary in the game, breaking the mold of beauty and decorum lingering from the 80s. Tokimeki Memorial is already a fairy tale, where teens just happen to believe in a superstition with the power to dictate their entire lives. The girls who look and act like barely bygone idols fit better into this fairy tale. A character like Ayako seems obviously meant to break free from it. Part of me believes this, even if I know that Ayako is still another object and ideal, a flattened representation of an artsy girl.

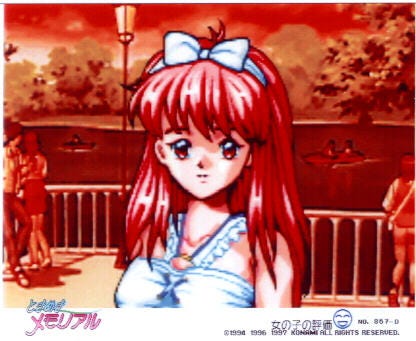

As I honed my ability to brush off girls I wasn’t interested in, there was one big outlier, and that’s Shiori Fujisaki. Shiori is the series flagship character and she alone smiles at you on the original box art. She bombed me and frowned at me too, but she doesn’t so much get in the way as haunt the character, and by extension me. Shiori is the only “canonical” love interest, if such a thing can be said about a game that asks you to choose between a dozen love interests. When you pick your character’s name, birthday, and blood type, you also select Shiori’s birthday and blood type. She is the only girl where the shape of her life is, even in this small way, under your control. The opening narration of the game explains that your character worked hard to get into the prestigious Kirameki High because that’s where his childhood friend, Shiori, is going. He sees her sitting at the front of his classroom and remarks that he’s had a crush on her his whole life and wants to become someone worthy of her affection. Instead of getting information on her from Yoshio, your character is the one to fill him in. Shiori can be in any club (it depends on what you pick as her birthday), she’s beautiful, well-liked, nice but not a pushover, and a top student. Her voice actress is phenomenal, giving a performance that’s sweet and feminine but nuanced and filled with enough personality that it does feel like she has known your avatar for years. The player character having a personality and desires outside of my input starts with Shiori. If I date any other girl, I am betraying his early dream to win over his lifelong crush.

I played the game in its entirely twice in a row. The first time, I had a very companionable relationship with Shiori, though never in tokimeki state. I walked home with her often and went on regular dates. The second time, I was mostly trying to keep her from being upset with me. Getting the Shiori ending is notoriously difficult. All of your stats, especially academic numbers, must be high. You have to get into a top college. Being so well-rounded will trigger meetings with most, if not every, girl in the game. And the more girls you know, the harder the game is. For most romance options, avoiding or delaying meetings is easy enough to pull off, but there’s no way to complete a “Shiori run” without juggling almost every female character. You can only become worthy of Shiori by becoming worthy of everyone. And then there’s the sad irony that in choosing someone else, she is not the one to reap the benefits of your quest for worthiness that she initially inspired. She will keep occasionally showing up outside after school. Even refusing to walk home with her doesn’t result in a penalty, it’s weirdly sad to turn her down. I am still reeling from the slight changes in the tone of her “sayonara” if you walk home alone. Not dating her makes the small coming-of-age sadness of your character loom large. You are either maturing past a childish crush or growing apart from one of your oldest friends. During my first game I took Shiori to the park and got a special scene where she reminisced about playing there together as children. To see that and know that I wasn’t even trying to win her heart was quietly devastating. I’d rejected many other girls, but none who shared history with me.

I’ve always hated the childhood friend trope in fiction. I think narratives that use it often ask me to believe in an emotional connection before the writing has done the work to justify it. I prefer to watch relationships develop from zero, or close to it. I have never had a childhood friend. I have never been anyone’s Shiori. It’s very easy to put myself in the shoes of one of the other girls, stacking themselves up against a decade or more of shared memories and in-jokes. As someone who has spent a lot of time outside, looking into the softly lit windows of others’ long and comfortable relationships, it’s easy to resent the implication of Shiori as the ideal.

It’s tempting for me to dwell on how my 2000s adolescence comes nowhere near Tokimeki Memorial‘s sweetness. It seems wonderful to be a girl who is held up as a wholesome ideal instead of being relegated to the weeds of rebellion, sex, and shame. The fantasy of a Shiori isn’t necessarily one of perfection and purity, though. Loving someone you’ve known for life is a fantasy of familiarity and certainty, a kind of personification of the safety you lose as you come of age. It’s a battle scar that anyone who has had to grow up can claim. Your character in Tokimeki Memorial is a teenager with an adult’s knowledge of compromise and regret laid over him through us, the players. Underneath the attractive archetypes and romantic trappings of Tokimeki Memorial, there is something much simpler, near universal. The true goal of the game is something we all have to do: make the most of your limited time. A girl standing under the tree is proof that you did.